example (physics)

Lots of people use Anki for learning languages or trying to memorize lots of facts in medical school. There are also lots of other uses, from learning to recite poems from heart to picking up programming languages. You can use it to connect faces to names if you're not a face person, memorize quotes to sound wiser than you are, or even how to tie knots. If you want an introduction to spaced repetition, Michael Nielsen and Gwern have great introductions. Here, though, I'm going to focus on making an easy-to-read, skimmable guide on how I've used it to study science and math.

The first and most obvious thing that I thought of memorizing with Anki are definitions. Definitions might sound arbitrary, but you'll need to know them if you're going to read papers. Often, definitions also point to very useful concepts for understanding the world--- and at the end of the day, it's this concept that you'll want to know. This is why I prefer cards asking me to define a term to cards asking me to give a term corresponding to a definition. Typically I prefer the "cloze typing" format for this.

I also like having go-to examples for my cards. I've found that examples connecting to the real world help me remember a concept and think more concretely about that topic.

I've found that a lot of expert intuition takes the form of knowing the relative sizes of various things. This is great for sanity-checking, making connections, visualizing, analogizing, and all sorts of other goodness. Knowing a single number is trivia, but knowing a web of numbers and their connections to each other is an intuition, or at least a useful part of one.

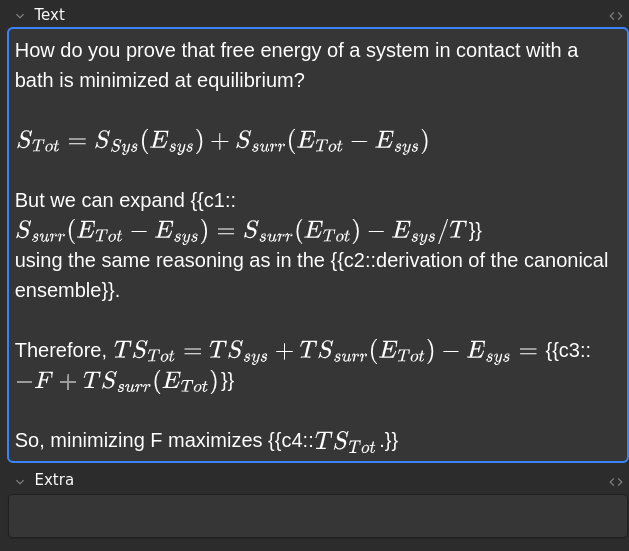

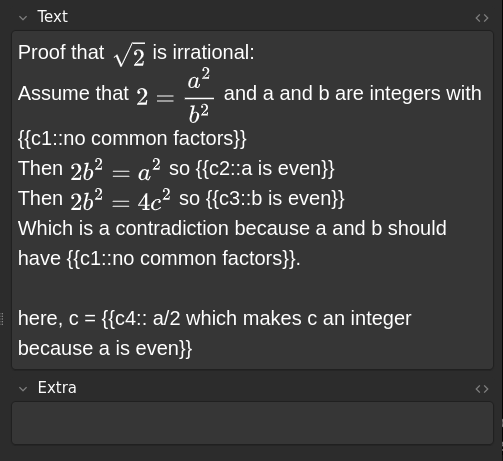

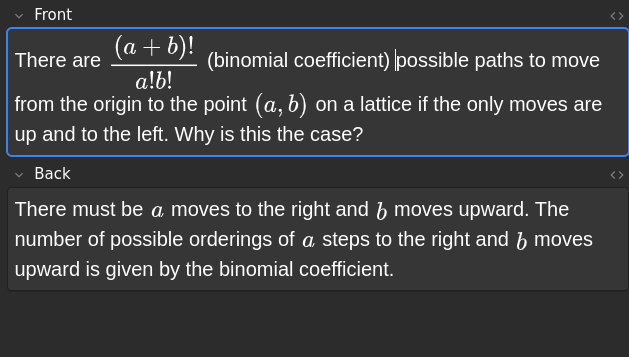

You can also use anki to memorize proofs, derivations of physical principles, or chain-of-thought reasoning by outlining the proof and using fill-in-the-blank (cloze) deletions on multiple steps. This means that you'll get quizzed on completing or justifying every step of the proof, given the rest of the proof as context. This can be tedious to make, and require a complete understanding of the proof, yet are *extraordinarily powerful* when done well. I can reproduce, entirely from my head, a proof for why the squareroot of 2 is irrational or the reason why minimizing the free energy of a system in the canonical ensemble is equivalent to maximizing the universe's entropy (and also the assumptions that go into these)

I learned this method from Paul Raymond-Robichaud

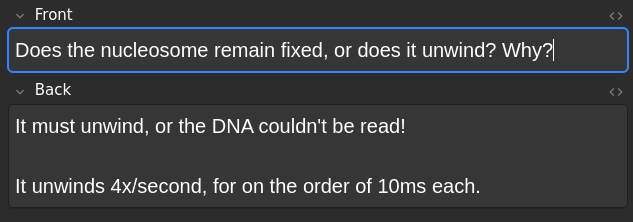

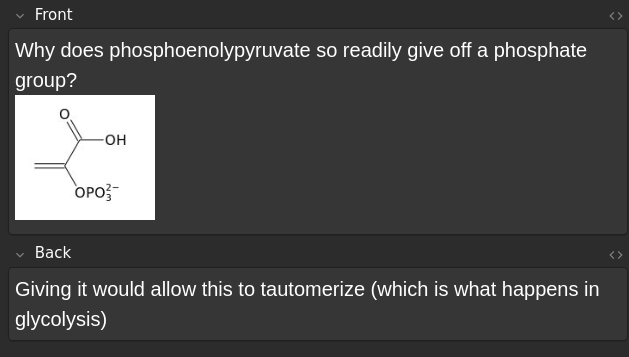

Another great thing to do is to memorize the *reasons* for why things are the way they are, which works great for algorithms and biology (anything which is, in some sense, designed to serve a certain purpose). You can also use these sorts of cards to tether formulas to intuitions.

My anki deck is a part of me. A piece of my soul resides within it. My memories may fade, time may shape me into a new person, but probably 90% of the cards I have now will remain unchanged. If there is some permanent essence of who I am, it has a .colpkg file extension.

Because of the permanency of my deck, I only put in things that I care about, things that I *want to become part of me*. I try to make sure that the information comes from a relatively credible source, such as a textbook, so I don't pollute my mind with falsehoods. Typically, if I read a textbook, I take (e)paper notes, then I convert the parts of the notes I think would make good cards into cards. I do this for lots of science and math stuff. I also try to do this when I read a paper.

Separately, I do use note-taking software (Obsidian) but there's very little overlap between what I put in my anki deck. Typically, I put things into my anki deck after I learn them, and I put things in Obsidian so that I don't have to learn them.

I typically use obsidian for taking notes that I can quickly reference. I mostly use it for things like documentation and arbitrary stuff (like what syntax means what in some python library). I don't put these in anki because although they're useful (for a short time) they feel shallow. I seek the truth about the world, and arbitrary facts, like which argument goes first in the python method isinstance(), doesn't actually point me towards any deeper truth.

A month after I started using Anki, I had a thought: "Wouldn't it be awesome if I could just memorize the structures of tons of molecules! I could end up making lots of connections between all of these and see things that others cannot!"

Unfortunately, this didn't work nearly as well as I thought. I did have the success of learning all of the most biologically-relevant amino acids, but then ended up getting extremely mixed up on trying to learn the different nucleotides. I tried cards along the lines of "draw X molecule from scratch" or "which molecule is this picture" and both were quite difficult if it had been more than a month. One I start adding new molecules I'm going to try formulating the cards to ask about the structure of a molecule in terms of another.

Anki works best when you review it every day. Reviewing it every day sounds like a daunting task, but I find my reviews fun. It usually takes less than 10 minutes and I feel like I'm sharpening my skills with every review. If it felt like a chore, I wouldn't have stuck with it. In fact, there were a few occasions where it did feel like a chore, and as soon as I realized that I wasn't looking forward to the reviews, I deleted all of the "problem cards". If it gets in the way of your fun, it gets in the way of your desire to review. If it gets in the way of your desire to review, it gets in the way of your frequent reviews. You must not dread anki; you must not treat it like a chore. If a card causes you to avoid reviewing, gouge it out and throw it away. It is better to give up on one card than to lose the benefits of spaced repetition forever.